Security sector: No transition without transformation

By Takawira Musavengana

“We are not going to give up our country for a mere X on a ballot. How can a ballpoint pen fight with a gun?”

Democratic transition has not occurred in Zimbabwe in spite of the fact that President Robert Mugabe and his party, the Zimbabwe African National Union Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF), have previously lost elections. And the reason is clear.

The security sector, which for the past decade or so has been running government affairs with Mugabe and others acting as a civilian facade, has not allowed the will of the people to prevail.

The so-called Global Political Agreement (GPA) – an inter-party agreement between ZANU-PF, and the two Movement for Democratic Change factions led by Morgan Tsvangirai (MDC-T) and Arthur Mutambara (MDC-M) – did not facilitate power sharing, but rather the retention of power by Mugabe, including a steady supply of political oxygen and a veneer of ‘legitimacy’, which he desperately needed in the aftermath of the March/June 2008 election period.

Like the 1979 Lancaster House Constitution, to the extent that it was negotiated by political elites without much reference to ordinary Zimbabweans, the GPA is a reflection of the bargaining power of the three parties.

It is an elite pact that was secretly negotiated by a coterie of individuals, who reported only to their party leaderships to the exclusion of their parties and elected members of parliament, let alone party members and ordinary Zimbabweans.

For this reason, the GPA is neither global nor reflective of the will of the 2,265,292 voters who participated in the presidential, parliamentary and local government elections of March 2008.

Whereas the two MDCs brought their respective electoral mandates to the negotiations, ZANU-PF brought a combination of an electoral mandate and control of the state, especially the security sector.

It is therefore not an accident that ZANU-PF ended up controlling all the ministries responsible for defence, intelligence and prisons. A nominal share of the ministry responsible for policing – Home Affairs – was secured by MDC-T at great pain.

Notwithstanding the provisions of the GPA that recognise the two MDC factions as partners in the Inclusive Government (IG), the state security sector remains opposed to – and has actively sought to undermine – the coalition government and maintain its own grip on power.

Ever since ZANU-PF started losing its electoral hegemony in the early 2000s, Zimbabwe has been under subtle military rule, with the Zimbabwe Defence Force (ZDF) operating much like a liberation army embedded in a ZANU of the 1970s and actively working for regime security.

In independent, 21st century Zimbabwe, elements of the state security sector still seem to subscribe to the view espoused by Mugabe back in 1976 – when he was the leader of ZANU and its liberation movement, the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA), and not President of the Republic of Zimbabwe – that “our votes must go together with our guns.

After all, any vote we shall have shall have been the product of the gun. The gun which produces the vote should remain its security officer – its guarantor. The people’s votes and the people’s guns are always inseparable twins.” (Meredith, 2008)

This overtly partisan and politicised approach is just one of the defining and troubling characteristics of Zimbabwe’s current civil security relations and the larger criminal justice system.

Other concerns include the security sector’s insubordination to legitimate civilian authority, selective application of the law to punish non-ZANU-PF voices, the accumulation of resources by a small politico-military elite through illicit exploitation of national resources, the militarisation of public institutions, and state-sanctioned violence and disregard for basic human rights (Hendricks and Musavengana, 2010).

These issues highlight the urgent need for change. Through covert and open interference with the democratic process, the state security sector has become the most potent threat to human security and democratic transition in Zimbabwe – and will continue to be so unless it is radically reformed.

Background

The images and discourse of violence that have dominated Zimbabwe’s polity for the past decade are in stark contrast to the jubilation and spirit of reconciliation of April 1980 when Mugabe took office as the leader of the newly independent state of Zimbabwe.

So promising were Mugabe’s first steps and the accompanying rhetoric that in 1994 – despite the Matabeleland massacres – the former colonial power, the United Kingdom, appointed him honorary Knight Grand Cross in the Order of Bath (only to strip him of the title in June 2008 when his true dictatorial self had emerged for all to see).

At the same time, institutions of higher education all over the world were falling over each other to confer honorary doctorates on him. He was also fêted by heads of state, kings and queens from countries far and wide, earning himself the nickname of Vasco da Gama at home.

But unbeknown to many, a violent and repressive one party state was under construction and reconstruction in Zimbabwe. As publicly acknowledged by Mugabe himself in his ‘degrees in violence’ speech, ZANU-PF’s (and Mugabe’s) propensity to resort to violence to resolve political differences and achieve political ends is neither new nor recent (Raftopolous & Mlambo, 2009).

Since the early years of independence in the 1980s, ZANU-PF and its government have enjoyed a monopoly of violence in Zimbabwe’s polity.

Against this background, today’s resurgent politico-military and economic complex, which is underpinned by violence and intimidation, has to be understood in terms of the undying desire by Mugabe to be life president, and by ZANU-PF’s quest to establish a one party state in Zimbabwe.

Zimbabwe’s security sector – comprising state security agencies such as the military, police and intelligence as well as non-state security structures, including war veterans and the ZANU-PF youth brigades of the 1980s and youth militias of the 2000s – has long been a willing and effective midwife to ZANU-PF’s political ambitions.

In 1982, the Gukurahundi massacres were preceded by Mugabe’s chilling speech to Parliament when he was Prime Minister and Minister of Defence. He said, “An eye for an eye and an ear for an ear may not be adequate in our circumstances. We might very well demand two ears for one ear and two eyes for one eye.”

And so it was that when the 5th Brigade was finally withdrawn from Matabeleland and Midlands Provinces after an outcry both within and outside Zimbabwe, an estimated 20,000 civilians had lost their lives and thousands more had been displaced. The findings of the Chihambakwe Commission of Inquiry into these events have still not seen the light of day (Hendricks & Musavengana, 2010).

In the first decade of independence, Joshua Nkomo’s PF ZAPU bravely stood up to and temporarily foiled ZANUPF’s one-party ambitions but not without paying a heavy price. By 1987, PF ZAPU had been violently battered into submission and forced to sign a Unity Accord, which effectively signalled the death of the party.

Constitutional Amendment No. 7 then created an all-powerful executive presidency, which marked the beginning of the end of the country’s nascent but promising democracy and, according to Welshman Ncube, turned Mugabe – the only occupant of that office since its creation – into a ‘myopic little village tyrant’.

Under the ‘united’ but largely unchanged ZANU-PF, Zimbabwe became a de facto one party state, effectively combining brute force, and the selective use and manipulation of the law to maintain its hegemony. The same scorched earth policy was to be used against the MDC two decades later culminating in the GPA in 2008.

Security Sector Governance

Throughout the post-independence years, cardinal principles of civil military relations have been sacrificed on the altar of political expediency in defence of ZANUPF’s hegemony. Profoundly partisan political statements and actions have come from the state security sector.

In 2002, the former Commander of the Zimbabwe Defence Force (ZDF), General Vitalis Zvinavashe, declared, “Let it be known that the highest office in the land is a straight jacket whose occupant is expected to observe the objectives of the liberation struggle. We will, therefore, not accept, let alone support or salute anyone with a different agenda that threatens (the) very existence of our sovereignty, our country and our people.”

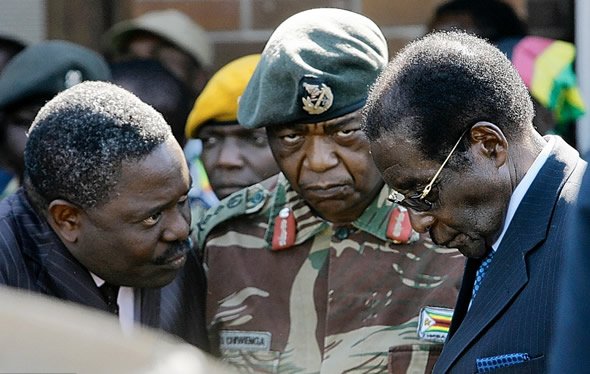

Not to be outdone, his successor, General Constantine Chiwenga, shocked the world in 2008 by saying, “elections are coming and the army will not support or salute sell-outs and agents of the West before, during and after the presidential elections … We will not support anyone other than President Mugabe, who has sacrificed a lot for this country.”

Senior members of various state security services have variously and publicly stated their support for Mugabe and ZANU-PF and their undisguised hatred for Morgan Tsvangirai, the MDC and all those opposed to ZANU-PF’s rule.

The rhetoric has continued even in the post-GPA period. Ominously, no one has been court-martialled for doing and saying exactly what state security operatives should not do or say in a constitutional democracy.

Unfortunately, over the last ten years as the security services crossed the line and instituted a subtle putsch, no regional or continental leaders have condemned the securocrats’ conduct either even though it is an affront to the principles and values of both the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the African Union (AU).

Although gaps exist in the law, the unorthodox conduct of the security sector has not been due to lack of relevant legislative and other regulatory instruments. The much-maligned and 19-times amended Lancaster House Constitution, the Defence Act and the National Defence Policy, among others, provide the appropriate legal and policy framework for the governance and management of the ZDF.

For example, the National Defence Policy correctly identifies cardinal principles of democratic control of the armed forces, including the defence force’s subordination to civilian authority; civilian responsibility for the formulation of defence policy with the technical assistance of the military; civilian responsibility for the political dimensions of defence policy; military execution of defence policy; non-interference of government and politicians with the operational chain of command; and, non-interference of the government and politicians in the application of the code of military discipline.

The same can be said about the police and prison services both of which are covered by reasonably far reaching legal and policy frameworks, which if fully and faithfully implemented, could make these services more human-security oriented.

In addition, the Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP) is an active member of the Southern African Regional Police Chiefs Cooperation Organisation (SARPCCO), whose code of conduct commits member police organisations to respect for human rights and the rule of law, service excellence and integrity, the fair and equal treatment of people, and the treatment of victims of crime with ‘compassion and respect’.

The code of conduct prohibits the police from inflicting, instigating or tolerating torture or other cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment. Yet, on numerous occasions, the ZRP in general and, what is known as, the law and order section in particular have been accused of – and found to be responsible for – violations of Zimbabwe’s laws and the SARPCCO code of conduct.

However, a major legal deficiency does exist in relation to the civilian intelligence services. The Department of State for National Security, which is commonly known as the Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO), is Zimbabwe’s main civilian intelligence agency.

It was inherited en bloc from the Rhodesian government and resides in the Office of the President under the political control of a Minister of State. Notwithstanding the fact that ‘democratic control of intelligence services should begin with the enactment of a clear and explicit legal framework’, the CIO is probably the only state security agency in Zimbabwe that is not established under the Constitution or any law.

The only significant mention of the Department of State for National Security can be found in the National Security Act, 2009 but only in relation to the inclusion of the department in the definition of ‘security services’, the Director General’s membership on the National Security Council and, for obvious reasons, the administration of the Interception of Communication Act.

Together with the chief of Defence Intelligence, the Commissioner General of the ZRP and the Commissioner General of the Zimbabwe Revenue Authority, the CIO Director General is authorized to access private post, eavesdrop on telephone conversations and intercept faxes and emails in the course of his work.

Despite these sweeping powers, in the absence of a ‘clear and explicit legislative framework’ the CIO is – from a financial, legal and policy compliance perspective – beyond the reach of judicial, parliamentary and public scrutiny (Hendricks and Musavengana, 2010).

Typically, the mandate of an intelligence service, such as the CIO, as a first line of defence would be limited to intelligence gathering.

“In the hands of responsible democratic leaders, intelligence is the major contributor to the state’s absolute obligation to its people to make sure that threats to security are detected in time for them to be counteracted, and for harm, death and destruction to be prevented.”

Unfortunately, the CIO is largely seen, and has acted, as the incumbent president’s secret police and been a major perpetrator of gross human rights violations, including abductions and the use of torture to extract information from political opponents, human rights defenders and ordinary citizens.

Clearly, the CIO has gone beyond the ‘state’s absolute obligation to its people’ and is engaged in party political work and involved in violence against the very people it is supposed to be protecting from harm. The pervasive politico-military and economic complex, which was informal in the 1980s and 1990s, was formalised in the 2000s through the Joint Operations Command (JOC).

The JOC is a throw-back from Ian Smith’s Rhodesia where it was created to coordinate state security agencies in the prosecution of the war against the resurgent guerrilla movement in the 1970s – a guerrilla movement that now forms the core of the ZDF.

As its name suggests, the JOC was designed to deal with operational military and security matters and not policy matters. Whereas the JOC initially operated under the “tacit management of the (ZANU-PF) party … By the time of the 2005 elections it was clear that the JOC was no longer an instrument of the state. It had become an alternative to the state, and was, in effect, a parallel government.” (Chitiyo, 2009:8).

It was ably and faithfully supported by a Central Bank, which, until the establishment of the IG and ZANU-PF’s loss of control of the Treasury, made funds available for party political purposes.

In addition to providing the required resources for extra-legal JOC operations, the Central Bank happily exceeded its monetary policy mandate and facilitated an extensive patronage and vote-buying strategy through the acquisition of agricultural equipment for new land owners, vehicles for Members of Parliament and even laptop computers and televisions for judges.

The entry of the JOC into politics was not by accident. It coincided with the formation of the MDC in 1999 and the new party’s electoral successes in 2000 and 2002, which indicated that ZANU-PF now faced a viable opponent for the first time since the demise of PF ZAPU in 1987, and even a government-in-waiting.

Between 2005 and 2008, as ZANU-PF’s political structures disappeared in the face of the MDC’s growing popularity, state and non-state security actors – including the so-called war veterans and youth militia – unleashed a violent proZANU-PF and anti-MDC campaign.

Without the active support of the JOC and a not-so-impartial election management body – under the leadership of a retired military officer, who has since been appointed Judge President – ZANU-PF would have done even worse than it officially did in the March 2008 elections.

Militarisation of Public Institutions

The last few years have witnessed the ‘Zanufication’of the public service, traditional leadership structures, youth training centres and the militarisation of public institutions. Serving and retired military, police and intelligence officials have been deployed to key public service positions.

These include the electoral commission, strategic grain reserve, the judiciary, prison services, permanent secretary positions in government ministries and heads of state enterprises (parastatals). Some have also joined politics and now serve as members of parliament, ministers and provincial governors.

On the face of it, there is nothing irregular with former state security officials retiring from active service and participating in politics and public life. It is in fact within their civic and constitutional rights to do so.

However, what is significant is the fact that ‘retirements’ from the security sector into civilian public institutions have been directly linked to the active pursuit of a partisan agenda – namely retaining ZANU-PF hegemony. The pronouncements and actions of newly deployed officials have clearly been tailored to advance a party political agenda.

Some of the effected institutions have since become avenues of economic plunder. The militarisation of public institutions also confirms ZANU-PF’s increasing lack of trust in professional public servants to guarantee the entrenchment project. An example of this phenomenon was the accusation that public servants, who were seconded to the electoral commission during the 2008 elections, may have rigged the elections in favour of the MDC.

This was the first time in the history of Zimbabwe that such accusations had been made by a governing party, which controls all facets of the electoral process. National youth service (vocational) training centres have also been converted into places where young people are indoctrinated with anti-MDC and pro ZANU-PF rhetoric.

In 2008 in particular, some of the national youth training centres were converted into torture camps, where opposition supporters were raped and beaten. Together with indoctrinated youths, groups of veterans of Zimbabwe’s war of liberation – including some who were far too young to be called veterans of anything – had earlier been at the forefront of the violent land dispossession campaign, with the support of the state security sector.

Confirmation of the youth militia-state security alliance was confirmed by interviews that were conducted in August 2003 with former militia members, who declared that, “we are ZANU-PF’s ‘B’ team. The army is the ‘A’ team and we do the things the government does not want the ‘A’ team to do.”

The Diamond Economy

The discovery of diamonds in the eastern parts of the country has proved to be both a blessing and a curse for Zimbabwe. It was a blessing because it came at a time when the country was on its knees and desperately needed a massive capital injection to breathe life into its crumbling economy.

The discovery happened in a season of ultra-high inflation, a worthless currency, violence and forced removals in towns and on commercial farms, hungry women fleeing to neighbouring countries with babies on their backs, and prisoners dying of disease and starvation.

Much was expected from this natural resource. But the discovery became a curse when the state security sector, the military and police in particular, turned the diamond areas into torture and killing fields, where local villagers were subjected to child labour, forced labour and wanton violence (Katsaura, 2010).

Launching a seminal 62-page report entitled, Diamonds in the Rough: Human Rights Abuses in the Marange Diamond Fields of Zimbabwe, Human Rights Watch noted: “The police and army have turned this peaceful area into a nightmare of lawlessness and horrific violence. Zimbabwe’s new government should get the army out of the fields, put a stop to the abuse, and prosecute those responsible.” Predictably, like all matters involving securocrats and human rights in Zimbabwe, no prosecutions followed.

Although the military has officially withdrawn from the diamond fields, and the Kimberley Process (KP) has approved the sale of some of Zimbabwe’s diamonds resulting in a motley collection of private companies involving themselves in the business, transparency and accountability are concepts altogether alien to the diamond trade in Zimbabwe.

Allegations of the military’s involvement in the illicit extraction and trafficking of diamonds through Mozambique, among other avenues, are still rife. To demonstrate the blatant lack of transparency in the trade, on 30 March 2010, a 13-member parliamentary portfolio committee on Mines and Energy was denied access to the Chiadzwa diamond fields.

This begs the question: if elected representatives constitutionally vested with the legislative authority of the country are not allowed to assure themselves and the nation that the country’s precious resources are in good hands, who retains that mandate and by what authority?

Recently, a kindergarten-esque dispute erupted between the Ministers of Finance and Mines, with the latter stating that US$174 million worth of diamond auction proceeds had been deposited with the Treasury, while the former argued that only US$62 million had been received. Apparently, even the president could not make sense of what had happened.

Just how US$112 million could disappear between these two ministries and how the discrepancy could not be sorted out by two colleagues who sit together at cabinet meetings every Tuesday boggles the mind, and raises the question: who, if not the fiscus, is benefitting from the diamond economy?

Could it be that the diamond economy has become a new vehicle for subverting the Treasury and funding extra-legal operations? Speculation is rife that the lack of transparency in diamond trading and the secrecy associated with the auctioning of precious stones and ongoing illicit exportation may in fact be feeding into ZANU-PF’s war chest in preparation for the next elections.

It has been argued in some quarters that apart from the president’s failing health and related succession battles in ZANUPF, and the quest to rid the government of the MDCs, one of the key factors motivating ZANU-PF’s desire for elections is the freedom from bankruptcy occasioned by the opaque diamond trade.

Indeed, the diamond proceeds have been an unprecedented political aphrodisiac for ZANU-PF. The recent upsurge of violence especially in rural areas aided and abetted by war veterans and ‘boys on leave’ – who are in fact military personnel executing an intimidation-filled pre-election campaign – falls within the JOC’s grand plan of retaining ZANU-PF at the ballot box and with it, preservation of the new-found wealth of the elite.

Is the Status Quo Unsustainable?

In response to the gap in the formal institutional architecture of civil military relations and the apparent violation of the precepts of civilian control of state security services, the GPA created a supreme policy making organ called the National Security Council (NSC).

The NSC was mandated with reviewing national policies on security, defence, and law and order; reviewing national, regional and international security, political and defence developments; considering and approving proposals relating to the nation’s strategic security and defence requirements; receiving and considering national security reports and giving general or specific directives to the security services; and, ensuring that the operations of the security services comply with the Constitution and any other law.

Thanks to a lack of political will and the security service chiefs’ undisguised disdain for non ZANU-PF elements on the NSC, the body has not fulfilled any of its major functions, especially that of ‘ensuring that the operations of the security services comply with the Constitution and any other law’.

And the JOC remains actively engaged in party political work. An analysis of successful reform or transformation in other parts of Africa – such as in South Africa – shows that the process was always premised on a broad consensus on the un-sustainability of the status quo.

Reform is as much a technical process as it is a political negotiation. It is critical therefore that the reasons why the security sector has run amok be fully understood and become part of the proposed interventions.

Reforming the security sector should be seen and done within the context of broader political and economic reforms. As illustrated above, the entry of the security sector into politics has been driven largely by the desire to maintain the hegemony of ZANU-PF for selfish reasons.

Contrary to the propaganda in the state-controlled media, the offensive has not been driven by altruistic or nationalistic intentions. It is about the retention of political power and the related fear of losing economic influence and wealth, most of it ill-gotten.

As the diamond case shows, unless transparency and accountability are entrenched in the extractive resources sector, the appetite of the security sector to remain permanently embedded in the political economy of the country will remain. However, at another level, it is important to note that the security sector is not a monolithic, single minded body.

Socio-economic and political privileges associated with the land, diamond and minerals economy have accrued only to a small but very powerful minority of politicians, senior public officials and securocrats.

The majority of low level military, police and intelligence personnel are professionals and patriots, who are obviously disillusioned with low salaries, politicisation of the security services and related non-merit based promotions that normally accompany partisan organisations, and the resultant loss of respect from the public.

The loss of opportunities to participate in international peacekeeping operations must weigh heavily on junior soldiers and their counterparts in the police since both services were involved in numerous missions prior to 2002. It is equally significant to note that most of the senior securocrats who purport to defend the ‘objectives of the liberation struggle’ are now old by military standards – in their mid to late fifties – and in the minority.

Although they have all passed the retirement date of either 20 years of service or 50 years of age as set out in their terms of office, their contracts continue to be renewed. But below them the ranks must surely now be dominated by born-frees given that it is 31 years since independence and considering the regular recruitment of born-frees, and natural and war-related attrition and retirements.

While the senior figures benefit from the current crisis, the majority of born-free personnel would surely stand to gain from a quick return to normalcy. South Africa, SADC and the AU March 2012 will mark a decade of South Africa’s involvement in mediating the electoral and governance crisis in Zimbabwe, hardly a success for the policy of ‘African solutions for African problems’ espoused by South Africa, SADC and the AU.

And unless reform of the security sector is addressed, the crisis and crisis-mediation could well continue for many years to come.

Returning the troops to the barracks and making the rest of the security sector professional will require the guarantors of the GPA – SADC and the AU – to tackle the security sector, through inter alia, peer to peer engagement with sister security services in the sub-region and the involvement of the appropriate technical structures of the SADC Organ on Politics, Defence and Security Cooperation – namely the State Security Committee, the Public Security Committee, the Defence Sub Committee and the Chiefs of Police Sub-Committee, through to the Ministerial Committee of the Organ and the Heads of States’ Troika.

It is disheartening that the South Africa/SADC mediation has not so far – at least publicly – acknowledged that the crisis in Zimbabwe refuses to go away not simply because of the so-called political leadership or political principals but also because of the intransigence of men and women in uniform, and their friends from the secret service.

Could this be an indication that SADC is unwilling, or does not yet have the know-how, to deal with intra-state security matters, particularly in relation to the human rights orientation of security services within countries?

What is clear is that the Zimbabwe crisis will not be resolved as long as SADC leaders stick to the organisation’s fawning respect for Article 4 (a) of the SADC Treaty on ‘sovereign equality of all Member States’ at the expense of Article 4 (c) on ‘human rights, democracy and the rule of law’ as principles governing the actions of SADC and its member states.

But the fact that security forces in the majority of SADC countries are not partisan and are not involved in, and do not interfere with, elections and other democratic processes provides a window of opportunity for mediation at the level of securocrats.

To the extent that the involvement in and the interference of the security sector with the democratic process in Zimbabwe touches on AU instruments, the AU’s Committee for Intelligence on State Security for Africa and the Peace and Security Council should be seized with the matter. However, South Africa remains at the centre of mediation on the Zimbabwe crisis and it is both a potential enabler and possible hindrance.

Under the African National Congress (ANC,) South Africa could be an enabler because of its significant political and economic might and the historical liberation camaraderie that links it with Mugabe in particular.

But historical liberation ties can also be a hindrance as both ZANU-PF and the ANC would be wary of a takeover in Zimbabwe by a non-liberation based political party – the MDC. The same applies to the governing parties in other potentially influential SADC member states – namely SWAPO (Namibia), Frelimo (Mozambique), MPLA (Angola) and Chama Cha Mapinduzi (Tanzania).

Significantly, the unwitting complicity of South Africa under former President Thabo Mbeki and subsequently under President Jacob Zuma in the unlawful involvement of the security establishment in Zimbabwe’s politics is evident in their dogged refusal to make public the report by six retired generals, who probed the orgy of violence that rocked the 2008 elections, and another by Judges Dikgang Moseneke and Sisi Khampepe on the 2002 electoral process.

By now it has become clear that progress in the mediation will only occur if:

1 The political risks and personal costs of intransigence are raised to a level which the parties to the GPA and securocrats cannot bear;

2 South Africa and SADC confront the elephant in the room and require compliance with regional and international best practice in civil security relations;

3 The mediation process is expanded beyond just South Africa to include an eminent African statesman acting on behalf of and facilitated by SADC

There is also a need for a coherent security sector strategy from the MDC. The Zimbabwe of today is much like the Zimbabwe of 1979/1980 or the South Africa of the 1990s where the security sector held the key to transformation. For this reason, the MDC must demonstrate more than a pedestrian understanding of the elephant in the room.

Even the ‘edited’ version of the outcome of the March 2008 elections demonstrated the popular mandate that the MDC received from the electorate. For a government-in-waiting and one that fully understands that the security sector is a key obstacle to democratic transition, the MDC’s lack of a known policy position on security sector transformation in the form of a draft national security policy, draft defence policy or draft intelligence policy, is cause for concern.

The cost of peace

Whatever the form that security sector transformation may take, the government’s empty coffers, coupled with lack of access to significant international capital, presents a major obstacle to reforms.

If the political will were to be found and SADC took responsibility for ensuring that the proposed package of political and economic reforms outlined in the GPA were implemented, including security sector transformation, then resources would have to be found to ensure that those who have overstayed their welcome retire into civilian life and give political progress a chance.

However, for that to happen, consensus and regional pressure must be generated on the unsustainability of the status quo and the inevitability of change. Recent political upheavals in North Africa provide a useful anchor and immediate window of opportunity for such consensus.

Mindful of recent developments in the international justice sphere, which have seen former strongmen such as Charles Taylor and Jean Pierre Bemba end up in the dock, fear of prosecution for the Gukurahundi massacres and other more recent human rights violations must be uppermost in the minds of those in the senior reaches of the state security infrastructure.

These fears have to be politically managed against legitimate demands for justice and accountability. Victims of state-sanctioned violence and impunity need redress, truth telling, apologies, criminal prosecution of culprits and compensation. But the longer the security sector remains embedded in the country’s politics and perpetrates more human rights violations, the slimmer the prospects of reconciliation and forgiveness on the part of victims.

And the slimmer the chances of credible elections and democratic transition. It is time for the guarantors of the GPA to provide leadership by tackling and reining in the elephant in the room – the partisan and politicised state security sector – as provided for in SADC’s own statutes and international best practices for civil, military and security relations.

If they do, then they will pave the way for real progress towards a new Zimbabwe. If they do not, then the will of the people will continue to be frustrated by the whims of the politicomilitary elite.

Some Recommendations

SADC and the AU should appoint a full-time mediator with sufficient political gravitas and establish a permanent African monitoring mechanism to monitor violations of the GPA and accelerate the implementation of key pillars of the GPA – such as a credible new constitution, election timetable, national healing and reconciliation, and security of the people and the ballot.

The international community should increase support for the constitution-making process, including political and institutional reforms, and reform of the criminal justice system, among other issues. The constitution making process provides a window of opportunity for genuine sustainable change and should not be allowed to slip away.

Through SADC, South Africa or the permanent mediator, influence should be exerted on the National Security Council to develop a new National Security Strategy for Zimbabwe and promote broader reforms of the security sector and related structures, including the prison services. Instructive lessons can be drawn from security sector transformation in South Africa and Ghana.

Zimbabwe should enact national policy and legislation governing the intelligence services, including legal and institutional provisions for executive control, and parliamentary and judicial oversight.

As part of political reforms envisaged in the GPA (and the new constitution), the Central Intelligence Organisation should be de-linked from the Office of the President and located in the public service under the political control of a minister, who should be accountable to parliament and the public for policy and budgetary matters.

There is a need to depoliticise and clarify the role of military veterans as well as providing them with socioeconomic recognition and opportunities so that they are not manipulated for partisan political purposes. Neighbouring countries such as South Africa and Namibia have established war veterans’ departments.

In South Africa, the department is housed under the Ministry of Defence. International support is required to enhance parliamentary and civil society literacy in relation to the discourse and oversight of security sector transformation.

No arm of the state should be beyond parliamentary scrutiny, hence the oversight, legislative and other functions of parliament should envisage and facilitate a robust and informed parliamentary engagement on all facets of the work of government.

Increased international and civil society support should be provided to SARPCCO to monitor and enforce compliance by Zimbabwean police officers with the SARPCCO Code of Conduct for Police Officials. An Elections Trust Fund should be established, which would be administered by UNDP.

The Fund would allow development partners to contribute towards the organisation and management of credible elections under a new constitution and within the framework of regional (SADC/AU) benchmarks for credible elections. The Fund would also support international and local monitoring of the electoral environment well before the day of voting.

The international community and SADC need to support the Organ on National Healing and Reconciliation to undertake effective national healing through, among other measures, truth telling, reparations, accountability, prosecutions and apologies.

The diamond economy needs to be unpacked to better understand the nature of the players in the industry, while additional mechanisms need to be implemented that will enhance transparency and accountability. The Kimberley Process has a critical role to play in ensuring that the diamonds do not become the source of, and fuel for, further conflict and violence.

Prosecutions under international justice system should be considered as an important line of defence, especially when individual securocrats decide to remain obstacles to democratic processes.

Professional security personnel, who through their sacrifices and patriotism, offer to defend the security of the state and citizens should be allowed to operate without being held to ransom by a few self-serving individuals.

==========================================================================

Takawira Musavengana is the Human Rights and Democracy Building Manager at the Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa in Johannesburg, South Africa. Prior to joining OSISA, he was a Senior Researcher in the Security Sector Governance in Africa Programme at the Institute for Security Studies in Pretoria, South Africa.

In 2010, he co-edited with Cheryl Hendricks, a publication: The Security Sector in Southern Africa. His forthcoming publication is entitled: The Case for a SADC Parliament: Old Wine in New Bottles or an Idea Whose Time Has Come?