2028 is the real crisis: Why Zimbabwe’s constitutional changes are about survival, not policy

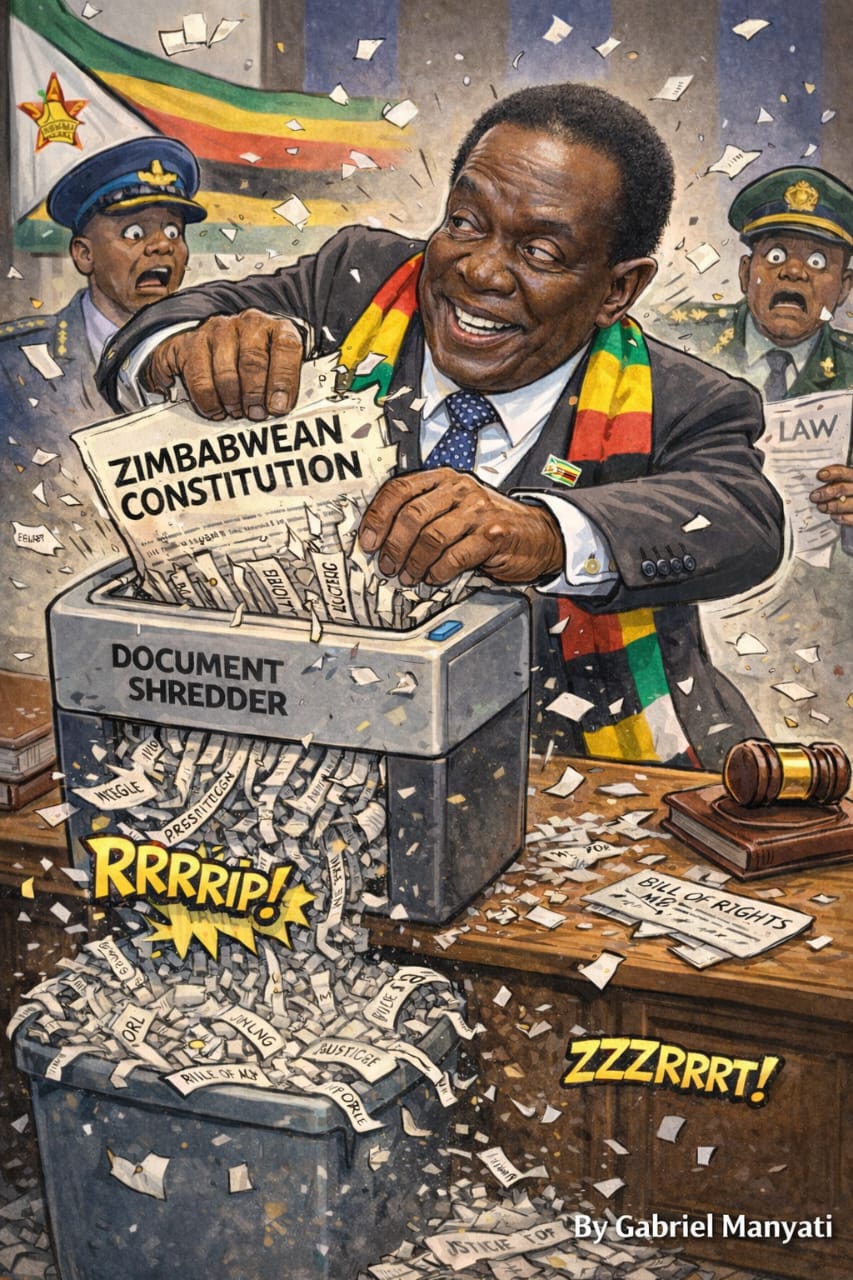

Elections in Zimbabwe often provide the backdrop to politics; succession is the symphony. To a casual observer, the current wave of constitutional amendments in Harare, including proposals to extend presidential terms from five to seven years and harmonise administrative functions, appears as routine bureaucratic housekeeping. Beneath this veneer, however, lies a calculated struggle over the one thing no autocrat has ever mastered fully – time.

President Emmerson Mnangagwa is not gazing towards 2030 as a visionary developer might. He is staring down 2028 with the eyes of a survivor. The 2028 election, enshrined in the 2013 Constitution, is more than a date on a calendar; it is a structural doomsday clock for ZANU PF.

By seeking to adjust the schedule now, Mnangagwa is attempting to freeze the pendulum before it swings back to strike him.

History in Zimbabwe is a brutal teacher, and Mnangagwa has been an attentive student. Robert Mugabe did not fall because he lost elections, although he had arguably been losing them for years. He fell because he lost the elite coalition that had sustained him for nearly four decades.

The securocrats, party elders and patronage kings withdrew their support once they judged he could no longer protect their interests. The floor collapsed beneath him. This lesson does not merely haunt the current administration; it dictates its every move.

Political science offers a framework for understanding this dynamic. Barbara Geddes, in Paradigms and Sand Castles, observes that the primary vulnerability of a dominant party is not the ballot box, but succession uncertainty.

When a leader’s exit date is fixed, the countdown begins. Subordinates stop looking at the leader and start looking at each other. Factions form, loyalties liquefy and the incumbent’s power begins to erode long before the moving trucks arrive at State House.

By pushing the horizon to 2030, Mnangagwa seeks to disrupt this factional coordination. He is signalling to ambitious rivals, most notably Vice President Constantino Chiwenga, the retired general who orchestrated the 2017 transition, that the seat is not yet available.

It is an effort to keep patronage networks tethered to the centre. If 2028 is the deadline, jockeying starts now. If 2030 is the deadline, rivals must remain patient.

Yet the logic of stability through extension is a dangerous illusion. Joel Barkan notes in Political Parties and Democracy in Africa that dominant parties survive through internal cohesion, which relies on a predictable ladder of promotion.

When the man at the top blocks the ladder, he does not create stability; he creates a pressure cooker.

The purges of Joice Mujuru, the 2017 Mnangagwa-Chiwenga tension, and ongoing factional manoeuvring are not anomalies; they are the natural consequence of a system where power is the only currency and the exit door is locked.

Supporters of these amendments cloak their arguments in the flag of developmentalism. They argue that major infrastructure projects and economic reforms require a consistent hand and that five-year cycles are too disruptive.

It is a seductive claim, often whispered in SADC corridors. Yet it ignores the reality that Zimbabwe’s economic malaise, including volatile inflation, a faltering currency and a manufacturing sector that struggles to stay afloat, stems not from short presidential terms but from a lack of accountability and systemic mismanagement.

The demographic tide is also turning against the liberation elite. Zimbabwe’s electorate is increasingly young, urbanised and unimpressed by credentials earned in the bush wars of the 1970s.

Michael Bratton observes in Voting and Democratic Citizenship in Africa that while a state can manipulate the mechanics of elections, it struggles to manufacture legitimacy once institutional rules are perceived as a personal plaything.

When a constitution becomes a tactical manual rather than a social contract, citizens grow restless.

Even within ZANU PF, there are signs of impatience. Reports from Harare, Bulawayo, and Masvingo suggest provincial leaders are quietly hedging their bets, cultivating networks outside Mnangagwa’s direct influence.

If the 2028 deadline is removed, these networks may accelerate factional manoeuvring rather than waiting obediently until 2030. In attempting to avoid the Mugabe fate, Mnangagwa may inadvertently be creating conditions for it.

There is a profound irony in a leader using law to circumvent the rules that legitimised his rise in 2017. Fully embracing the 2013 Constitution would have signaled the New Dispensation’s departure from strongman politics.

To amend it now is to admit that the system cannot survive its own rules.

Investors, whom the government courts with the mantra “Zimbabwe is Open for Business,” are unlikely to be reassured by a nation that rewrites its foundational laws to suit the lifespan of its leader.

Capital seeks predictability, and there is nothing predictable about a country where the clock of power is manually adjusted whenever it suits the incumbent.

It is important to acknowledge that Mnangagwa may genuinely believe longer terms provide policy continuity, especially in infrastructure and economic planning.

Even if this is part of the calculus, it is secondary. The primary driver remains survival. The amendments are prophylactics against internal coups and elite fragmentation.

Ultimately, the 2028 crisis is a crisis of confidence. ZANU PF, despite its control over state media and security organs, is terrified of what happens when the music stops.

Citizens are told these amendments are about continuity. Continuity of what, though? If it is continuity of elite enrichment at the expense of institutional integrity, 2030 will not be a year of celebration but a year of reckoning.

Mnangagwa may succeed in moving the clock, but he cannot stop the sun from setting.

The most provocative truth of Zimbabwean politics remains: a leader’s greatest threat is rarely the person holding a ballot, but the person standing directly behind him.

By attempting to outsmart 2028, Mnangagwa may be giving his rivals more reasons to abandon patience and start planning their own paths to power.

Constitutional amendments may change dates, but they cannot change ambition.

Gabriel Manyati is a Zimbabwean journalist and analyst delivering incisive commentary on politics, human interest stories, and current affairs.