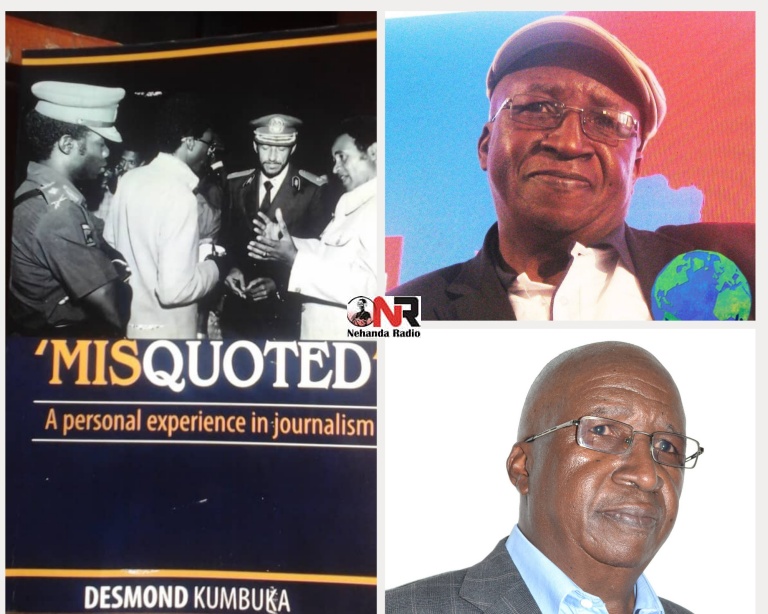

‘Misquoted’: A journalist’s nightmare

By Memory Chirere

Desmond Kumbuka indicates in the blurb of “‘Misquoted’: A Personal Experience in Journalism” (2020), published by Passpoint Publishers Private Limited, that the book is “not a journalism textbook and does not pretend to be one.”

I agree with him entirely. I, however, think that this memoir becomes many other things, becoming even more useful than the ordinary journalism textbook.

This is a story about what journalism has taught one man. It is a story about the good and bad goings on in the backstage of journalism.

For those into media studies in Zimbabwe, and the connoisseurs of journalism in the country, Kumbuka’s book offers what I could call an intelligent peek into the “who is who” in the media in Zambia and Zimbabwe, in the past 40 years.

The rich thread takes you from the mournful doe-eyed Emmanuel Nyirenda, the irascible Vincent Mijoni, Adam Hamiwe, Giles Kuimba, Eric Richmond, Keith Simpson, Bill Saidi, Tonic Sakaike, Gilbert Mawarire, Stephen Mpofu, Davison Maruziva, Bester Kanyama, Douglas Takundwa, Chen Chimutengwende, Willie Dzawanda Musarurwa, Bornwell Chakaodza to Geoffrey Nyarota, among many others.

It is more of an evaluation sheet through which you see the rise and fall of an array of characters and organisations in the local media.

I could not put this book down from the moment I first held it. Sometimes I took a break just to laugh, or shake my head in disbelief.

Here is a book that reads like “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer”.

A book with the capacity to arm many young journalists with the dos and don’ts of journalism, albeit in very subtle ways.

In this story, the hero (Kumbuka), seems to be always falling into one misfortune after another, just like Pimbirimano from the Shona folklore; but always getting out of trouble through his own resourcefulness, only to fall into a much bigger misfortune — on and on, without the possibility of a happily ever after.

Look at this: Sometime in 1976, young reporter Desmond Kumbuka, who is coming from a nasty pub fight, walks home with a very ugly black eye.

He is asked by his editor to attend a Press conference at President Kenneth Kaunda’s State House. To hide this embarrassing injury, Kumbuka hurriedly acquires a pair of dark glasses on the streets of Lusaka.

But President Kaunda singles out the suspicious young man with ill-fitting dark goggles in the crowd, and loudly offers to help him acquire appropriate spectacles.

The president genuinely thinks that the young journalist has a real eye problem.

Later, Kumbuka writes a letter thanking Kaunda for his kindness, for he went to see the offered eye specialist.

But Kaunda is not done.

He writes back to poor Kumbuka, saying the young man’s letter was sincere and that, “I (Kaunda) value your letter so much that I am asking you to sign it, for you forgot to do that. I would wish to have it back for my personal file.”

Journalists rarely receive such attention from heads of State.

It is while at the Zambia Daily Mail that Kumbuka is accused of misquoting the Police Commissioner of Zambia, Fabiano Chela.

Kumbuka’s story had made it to the front page of the daily, claiming that the commissioner said the Zambian police force was full of criminals!

The tragic headline read: “Criminals recruited in the Police Force — Chela.”

Kumbuka is dragged before the feared police boss, regardless of the fact that the commissioner himself had told Kumbuka that “it is very possible (that criminals could be recruited into the Zambian police).

“We are not God. So how would we know whether one has criminal tendencies, unless they have a criminal record on our data-base? It is possible to recruit criminals as police officers. . . ”

Kumbuka is instantly dismissed from the Zambia Daily Mail.

And the lesson learnt?

“In the complex game of politics and corporate gamesmanship, it is not uncommon for a supposedly responsible national leader . . . to vigorously, and usually with a straight face, disown reports of actions or words attributed to them in the media, if such reports or actions expose them. . .”

Kumbuka also admits somewhere in the book, which reads like a thriller, that; as a young journalist, he had the rather romantic notion found in most young journalists that a good reporter is a brusque, rough living, hard-drinking, and roguish character.

He should cause the authorities headaches with probing and incisive questioning, and articles that leave government officials with the proverbial egg on their faces.

He admits to having a long affair with crime literature, through reading the likes of Spaghetti thrillers, James Hardley Chase, Mickey Spillane, Oliver Strange, Wilbur Smith, Mario Puzo and others, leading to his love for crime reporting.

At some point Kumbuka would join the police during their patrols, so that he is acquainted with the crimes and the criminals he so much liked to write about.

Clearly, this means a reporter ought to have an inherent interest in an area of his chosen specialisation.

However, discipline was not one of Kumbuka’s strong points.

In his next post at the Mining Mirror, a newspaper based in Mufulira, a small mining town bordering the then Zaire and Zambia, Kumbuka joins colleagues to drink regularly across the border in Mokambo.

They would have good times with buxom Congolese women “with their ample bosoms and rather accommodating proclivities.”

It turns out that the guys are spending proceeds from the sales of the paper, with the hope of repaying the following Monday, which was a payday.

On a Saturday, way before payday, the Editor-in-Chief in distant Ndola, instructs them to bring the money to Ndola “right now!”

Kumbuka and his colleagues get fired for it. He is back on the streets and the misery of a man in a foreign country is evident.

But Kumbuka’s life has not only known the downturns, which include sleeping in the open and in noisy 24-hour bars due to lack of accommodation. Life has taken him to many respectable stages. It is a life well-lived.

After Zimbabwe’s independence, Kumbuka finds himself at The Sunday Mail in Harare, where he quickly establishes himself as a reporter and columnist.

He later takes over from Henry Maarsdop, a prolific columnist, who penned a popular Sunday column called “Henry Maarsdop on Sunday.”

Kumbuka’s own column became known as “Muongorori’s View”, and it ran side-by-side with the one by Maarsdop.

For several years, Kumbuka branched off into public relations.

At the inception of the Associated Newspapers of Zimbabwe (ANZ), he founded The Express Newspaper in Chitungwiza along with several other weeklies.

He also found himself at what became the Daily News and Daily News on Sunday.

Prior to his stint with ANZ, Kumbuka was also involved in the establishment of another newspaper, the Daily Gazette for which he was deputy editor.

It is interesting that although Geoffrey Nyarota ably edited this book alongside Ruby Magosvongwe of the University of Zimbabwe, Nyarota himself is not spared in this book.

He is given his due; praised here and blasted whenever Kumbuka thinks it is necessary.

That Nyarota has allowed this to stand as it is, is a plus for him!

“‘Misquoted’: A Personal Experience in Journalism” (2020) is the most informative book that I read in 2020. The Herald