Zanu PF choir master no more

By Maxwell Sibanda

As black Zimbabweans fought their last battles against the colonial Ian Douglas Smith-led Rhodesia Front (RF) in the 1970s, music had become part of the revolution.

In the rural areas, the masses would gather during the night for all-night pungwes (open-air political meetings) where freedom fighters educated them about the war, as well as boost their morale through song and dance for most of the night.

The singing was not just a whisper — it was loud. And in the silence of the night the music could be heard far away.

The music was radical in nature, challenging the status quo and stirring political consciousness among the masses whose repulsiveness against the colonial system became legendary.

It was a rude awakening for the brutal colonial regime, which used to believe in the magic bullet theory whereby the masses were only supposed to absorb its reckless propaganda without question.

Music became a useful tool to speak out against the excesses of the Smith regime and rallying the young and old to support the liberation struggle, which eventually forced the minority white government to the negotiating table.

The music was rich, spiritual and lamented the racial inequalities. With the masses becoming aware of their sorry situation, the elders and youths were bound together in the fight for justice and equality.

The singing was direct: some of the songs urged youngsters to join the liberation war and fight for justice; other songs mocked those in authority, while some were joyous choruses, with others appealing to the ancestors for divine intervention.

Zimbabwe’s liberation struggle thus gave birth to a new artistic genre — protest music.

In neighbouring Mozambique, where the freedom fighters had established their headquarters, a radical pirate radio station — The Voice of Zimbabwe — was launched by the Robert Mugabe led Zimbabwe African National Union Patriotic Front (Zanu PF) political party so as to boost the morale of fighters and participating masses.

A popular programme on that radio station, Chimurenga Requests used to broadcast revolutionary messages and liberation music.

The launch of this pirate radio station led to the formation of several choirs and bands within the armed forces that specialised in developing music for the struggle. The songs were popular with the masses as they were also sung by the liberation fighters during the pungwes.

The Voice of Zimbabwe, although banned in then Rhodesia, became a hit within black communities and in liberation fighters’ camps as it updated them on the war’s progress.

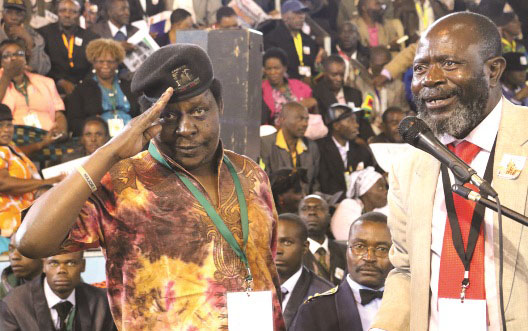

Among the popular Zanu PF choirs was one led by the late Dickson Chingaira popularly known as Cde Chinx, a former liberation fighter who composed and sang liberation songs.

The veteran choir master died on Friday at the age of 61.

He was the prince of Chimurenga music deep inside the bushes where the struggle for independence was executed. Back home, another deep voice of resistance against white minority rule could be heard in the form of one Thomas Tafirenyika Mapfumo.

But talk of songs that moved young men and women to take up arms; believe in their capacity to dethrone the colonial regime which was armed to the teeth and even give up their lives to free Zimbabwe from the yoke of colonialism, Cde Chinx beats them all.

He joined the Zimbabwe liberation war in 1975, as an exuberant combatant operating in Mozambique where he led Zanu PF’s (Leopold) Takawira Choir, which entertained recruits in camps so as to keep morale high. He was trained as a political instructor.

Some of his popular songs include Maruza Imi, Sendekera Mukoma, Chimurenga Chakarwiwa ne Zanu PF and Shungu Dzedu.

In one of his interviews Cde Chinx explained the role of music during the war.

“War was not a dinner party. Any minute one could die. The enemy wanted to kill us and death was everywhere. To make matters worse, the enemy was armed to the teeth…

“There was need to make people feel at home even if death was everywhere. That is where music came in. It was the lubricant of the revolution.”

He said he composed songs to fit different situations.

“We had songs that we sang after hitting the enemy. We had songs to lift the morale of the masses, especially after the enemy had destroyed their homes and killed their cattle. We had to make people realise this was a war, make them strong and committed to the struggle despite the difficulties and the losses.

“We had songs that we sang to dispel lies that were being churned out by the Smith regime. You see, the regime would broadcast lies on radio saying they had killed thousands of comrades yet we would have killed dozens of them. So we had songs to tell the masses that the enemy is a liar.

“We also had songs to encourage our neighbours so that they could keep on supporting and assisting us in the struggle.

“The enemy would lie that we are divided so that those who were assisting us would think they were supporting a lost cause.”

After the war, Cde Chinx came back home to a star performance alongside international reggae music superstar (the now late) Bob Marley at Rufaro Stadium in Harare.

Cde Chinx was also there leading the Zanla Choir as he warmed up the stage for Marley’s performance. And he sang a song to Prince Charles: “Prince Charlie, get our message to your mother, the Queen (of England). Say Zimbabwean people were the happiest in the world on this day 18 April 1980. You better get our message…”

After achieving notable success as a war songwriter and singer during Zimbabwe’s liberation struggle, Cde Chinx stepped to the forefront to make a personal statement with his singing prowess.

He formed the People’s Choir and immediately released congratulatory songs Nerudo, Zvikomborero, Roger Confirm and Ngorimba.

When members of the People’s Choir went their way, Cde Chinx formed the Barrel of Peace before joining Ilanga as a vocalist. He later turned solo and in 1999 released the album Gedge Yaramba.

He also played Rapo, in the 1996 film Flame, about the Zimbabwe liberation war.

Flame, the first feature from British-born film maker Ingrid Sinclair, takes on the age-old issue of image versus reality in war.

The events related in this film transpire during the 1970s, when the whole country was engulfed in war. Music is also central to the film and Cde Chinx plays the choir master.

In this role he essentially plays himself — a famous choir master and fighter.

In 2001, Cde Chinx, who was working at ZBC participated in the government commissioned album Hondo Yeminda Volume 1 & 2 and features in most of the album’s videos. During recordings he was backed by the State-owned Police Band.

After spearheading the recording of propaganda musicals for the ruling party, Cde Chinx was in 2005 man-handled and beaten by the police after he fired shots into the air as the police destroyed his Harare mansion during the government initiated operation Murambatsvina in which hundreds of homes were razed to the ground.

The police could not spare Cde Chinx his structure, and President Robert Mugabe later scoffed at the musician’s attempt to block the destruction of his house. His participation in songs that heaped praises on the chaotic land reforms in support of Zanu PF made him a friend and foe alike.

To Zanu PF sympathisers, he became one of the party’s staunchest defenders but exactly the opposite with those who were fed up with Mugabe’s regime.

From then on, his music career took a turn to the worst, with the worsening economy; ill-health and the rise in other alternative genres also contributing to his loss of popularity.

Towards the end of his life, his failing health became an albatross around his neck as he could no longer perform at shows, including at Zanu PF sponsored events.

Married to Patricia and Ntombizodwa, in the later years Cde Chinx’s health began to deteriorate as he battled cancer and at the time of his death was wheelchair bound.

He became a charity case, with sympathisers stepping in to help him out whenever they could.

Among the good Samaritans was is one Joseph Nyadzayo, the Zimbabwe Music Awars (Zima) chairman, whose contribution is probably one fine story of generosity Cde Chinx would like to share with his Maker who ended his life yesterday.

Nyadzayo’s Zima gave Cde Chinx a house for his contribution to music and the liberation struggle.

The musician was presented with keys to the house during the 2014 Zima ceremony held at the Harare International Conference Centre but the house could only be availed this year, a few months before his death.

With his death, the music industry has been robbed of another legend, whose contribution to the liberation struggle and the music industry is beyond reproach.

Roger! Roger! Roger!

It’s so sad because he can no longer respond in the affirmative, “confirm”, because he has been silenced by death.

Rest in peace Cde Chinx.