Queen Nadia TV: Shock travels faster than thought, and nudity travels faster than argument

I wrote briefly about this issue a few days ago, but time did not allow me to fully develop my thinking. The matter is too important, and the arguments too often reduced to slogans, to be left half-explored.

I therefore return to it in the interest of expressing my views more fully and more carefully, not to inflame for its own sake, but to clarify what is increasingly being muddled in public discourse.

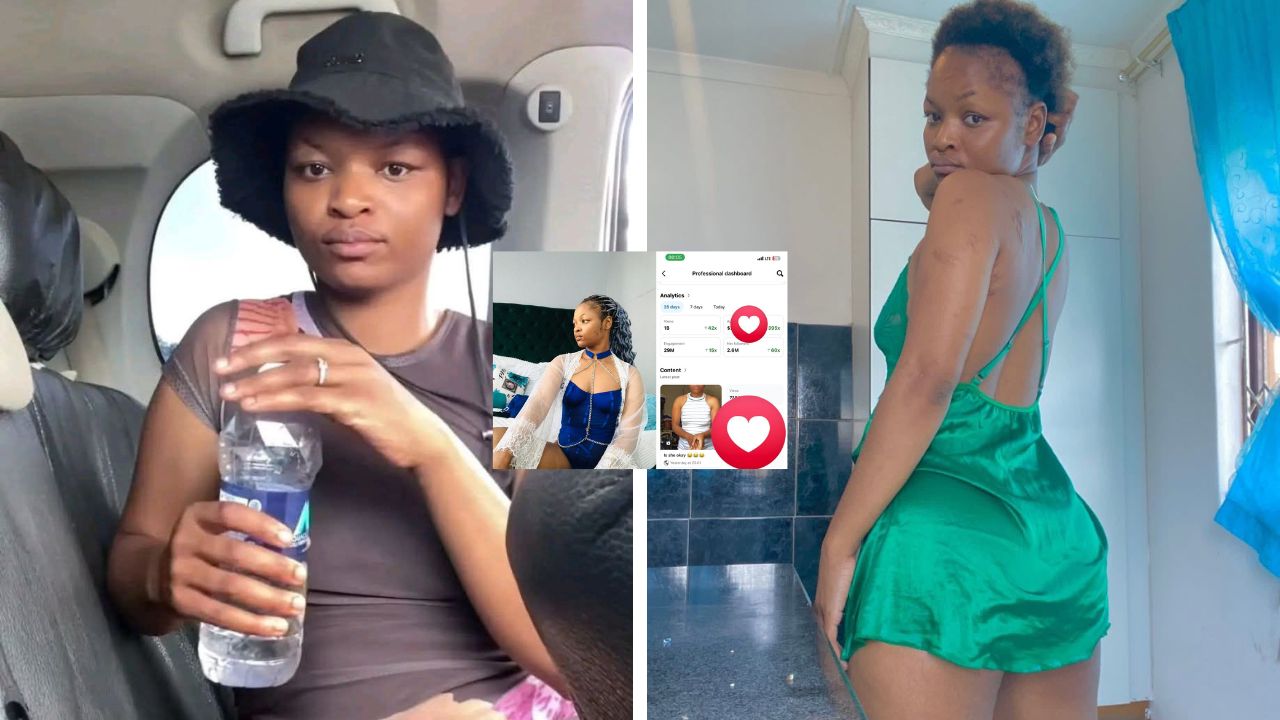

The controversy around the Zimbabwean influencer known as Queen Nadia TV has been framed by her defenders as a simple battle between freedom and intolerance.

She posts explicit sexual content on Facebook, a platform used by children, families, churches and workplaces, and when challenged she invokes a familiar mantra: “don’t live for people”. Her supporters applaud what they call authenticity and courage.

But beneath the noise lies a basic conceptual failure. Personal morality and public decency are being collapsed into one, and that collapse is intellectually careless and socially dangerous.

Personal morality is private. It belongs to the inner life of the individual. It is shaped by belief, experience, rebellion, faith, trauma and reflection. It governs what one considers right or permissible for oneself, especially when no-one is watching.

Public decency is not private. It is collective. It is the minimum standard of behaviour required for strangers to share space without violating one another’s dignity. A society that cannot distinguish between the two gradually loses the ability to regulate itself.

Public decency is not about moral purity. It is about restraint. Roads, classrooms, markets, churches and digital platforms are not extensions of the private bedroom. They are shared rooms.

The rules that govern them are necessarily stricter than those governing private life because they must protect the vulnerable, the unwilling and the unconsenting.

A child scrolling Facebook did not consent to sexual exhibition. A parent did not consent on that child’s behalf. Public decency exists precisely to manage such asymmetries of exposure.

Personal morality, by contrast, does not require agreement. One person may view nudity as empowering or artistic. Another may see it as degrading or corrosive. Both positions can be sincere.

The problem begins when one individual insists that their personal moral choice must be accommodated in public regardless of who is harmed, offended or coerced into exposure. At that point, morality ceases to be personal and becomes tyrannical.

The slogan “don’t live for people” – which I saw Nadia’s page – sounds rebellious, but it is philosophically thin. No human being exists outside society. Language, money, law, technology and platforms are social creations.

To benefit from these collective systems while rejecting the obligations that come with them is not freedom. It is free-riding. Broadcasting oneself on Facebook while dismissing the social norms that make Facebook usable is a contradiction, not an act of courage.

Criticism is often dismissed as oppression. This is another category error. To argue that explicit sexual display violates public decency is not to dictate what someone must believe about their body or sexuality.

It is to insist that some expressions belong in private or age-restricted spaces. Boundaries are not evidence of fear. They are evidence of wisdom. Every functioning society draws lines.

The only question is whether those lines are drawn thoughtfully or abandoned in favour of whoever shouts loudest.

At this point the debate is often sanitised by pretending the behaviour is purely expressive. It is not. It is economic. Social media platforms reward attention. Views generate reach. Reach produces engagement.

Engagement translates into money, whether through Meta monetisation, brand leverage or algorithmic amplification.

Repeated sexual exhibition in public feeds is not accidental. It is calibrated for clicks. Shock travels faster than thought, and nudity travels faster than argument.

This matters because it exposes the dishonesty of the “don’t live for people” slogan. If one’s income depends on views, shares and comments, then one is quite literally living off people. The audience is not incidental. It is the business model.

To then dismiss that audience’s objections as irrelevant is not principled defiance. It is biting the hand that feeds you while demanding applause for doing so.

There is an even more uncomfortable layer that defenders rarely confront. The average adult male is already saturated with pornography. The digital age has normalised a level of sexual consumption unprecedented in human history. This has not produced sophistication or liberation.

It has produced desensitisation and compulsion. In that context, the fascination with blatant, mindless nudity is less a sign of empowerment than of exploitation. It feeds an addiction that algorithms are only too eager to monetise.

Popularity is not a moral argument. Sugar sells. Drugs sell. Outrage sells. Sexual imagery sells. The fact that many engage with such content does not make it healthy or harmless. Algorithms do not care about human flourishing. They care about time on screen.

When explicit content is defended on the basis of engagement, the argument has already conceded its emptiness.

Defenders often retreat to a final line of defence: if you do not like it, scroll past or block her. This argument sounds reasonable until one examines it closely. Scrolling past is not neutral.

Repeated exposure to explicit imagery in public feeds normalises indecency, trains attention towards objectification and dulls social sensibilities over time.

Blocking is reactive, not preventative. Public decency does not operate on the principle of individual avoidance. It operates on collective responsibility.

Social media is not a private room one enters by invitation. It is a public square governed by algorithms that push content into feeds whether users want it or not. Children do not curate their feeds with philosophical care. Parents cannot monitor every scroll.

To tell critics to scroll past is to surrender the public square to the most sensational and monetarily incentivised content creators. It is an abdication of civic responsibility.

Context also matters. Zimbabwe is a society where extended families share devices, where economic pressure compresses generations into small living spaces, and where digital literacy is uneven.

To insist that repeated sexual exhibition in such an environment is merely a personal choice is to ignore reality. Choices do not exist in isolation. They land somewhere. And where they land matters.

There is a deeper irony here. Those who equate exposure with empowerment misunderstand both. Real agency requires discipline. When attention becomes currency, the self becomes a commodity. The algorithm rewards escalation, not depth.

What begins as defiance often ends as dependency. In this sense, public decency is not the enemy of freedom but its guardrail. It protects individuals from being consumed by the very systems they believe they are mastering.

None of this requires religious panic or moral hysteria. One need not quote scripture to argue that public sexual exhibition on a general platform is inappropriate. The argument stands on civic grounds alone.

A society is not a collection of isolated wills. It is a network of obligations. Public decency is the etiquette of freedom. It allows pluralism without turning shared space into a battlefield of impulses and egos.

When asked who decides what is decent, the answer is uncomfortable but unavoidable. We decide together, imperfectly, through law, custom, platform rules and social pressure.

These mechanisms are flawed, contested and often misused, but they are preferable to a world where the most shameless or best monetised set the standard. When everything is permitted in public, nothing is protected.

The mature position is neither censorship nor celebration. It is clarity. One may live by personal beliefs in spaces designed for consent and choice.

But the moment one steps into a public square, physical or digital, obligations accompany rights. That is not oppression. That is adulthood.

A society that forgets the difference between personal morality and public decency does not become freer. It becomes confused. And confusion is fertile ground for exploitation, by algorithms, by markets, and by those who have learned that shock pays better than substance.

The real rebellion today is not exhibitionism. It is restraint.

The real courage is not shouting “don’t live for people”, but asking how to live with them without selling dignity for clicks.

Gabriel Manyati is a Zimbabwean journalist and analyst delivering incisive commentary on politics, human interest stories, and current affairs.