ROMEO TAOMBERA ZIBANI

versus

JUDICIAL SERVICE COMMISSION

and

HIS EXCELLENCY, THE PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF ZIMBABWE, CDE ROBERT GABRIEL MUGABE N.O. and MINISTER OF JUSTICE AND LEGAL AND PARLIAMENTARY AFFAIRS, HON VICE PRESIDENT EMMERSON DAMBUDZO MNANGAGWA N.O.

and

CHIEF JUSTICE GODFREY CHIDYAUSIKU JA

and

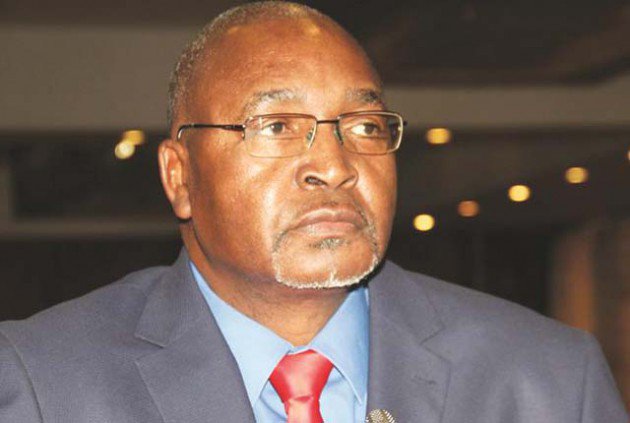

DEPUTY CHIEF JUSTICE LUKE MALABA JA

and

HONOURABLE JUSTICE RITA MAKARAU JA

and

HONOURABLE JUSTICE PADDINGTON GARWE JA

and

HONOURABLE JUDGE PRESIDENT GEORGE CHIWESHE JP HIGH COURT OF ZIMBABWE HUNGWE J HARARE,

12 DECEMBER 2016 Urgent Chamber Application S Hashiti, with him J Samukange, for the applicant ABC Chinake, for the 1st respondent E Mukucha, with him M Chimombe, for the 2nd & 3rd respondent No appearance for the 4th-8th respondent HUNGWE J: The Constitution of the Republic of Zimbabwe Amendment (No. 20) Act, 2013 repealed and substituted the Constitution of Zimbabwe that had been in operation from 18 April 1980.

The new Constitution ushered a silent revolution both in terms of the prominence it gave to the recognition of national objectives and good governance. In this regard the first chapter is dedicated to the Founding Provisions amongst which feature the supremacy of the Constitution as well as the founding values and principles.

The first chapter emphasises the supremacy of the Constitution and the rule of law, fundamental human rights and freedoms, recognition of equality of all human beings, gender equality and good governance.

The principles of good governance, which bind the State and all institutions and agencies at every level, include respect of the people of Zimbabwe from whom the authority to govern is derived.

One of the fundamental founding value and principle is transparency, justice, accountability and responsiveness.

The duty to respect fundamental human rights and freedoms is repeated in s 44 which provides that the State and every person, including juristic persons, and every institution and agency of the Government at every level must respect, protect, promote and fulfil the rights and freedoms set out in the Constitution.

FACTUAL BACKGROUND OF THE APPLICATION

The applicant, a private citizen and a student of law at the University of Zimbabwe, seeks a provisional order couched in the following terms; “Terms of the Final Order Sought That you show cause to this Honourable Court why a final order should not be made in the following terms:

1. The process which has been put in motion by the first respondent for the interview of candidates to be considered for appointment to the office of the Chief Justice of Zimbabwe be hereby suspended pending the finalisation of the proposed amendment to Section 180 of the Constitution of Zimbabwe.

2. That cost of suit be borne by any such party who opposes this application on an attorney and client scale.

Interim Relief Sought Pending determination of this matter, on the return date, the following relief is granted:

1. That the first respondent be and is hereby interdicted from conducting interviews set for the 12th December 2016 which interviews are for the ostensible purpose of submitting names to the President of the Republic of Zimbabwe for his consideration in appointing the Chief Justice of Zimbabwe.”

In his founding affidavit the applicant states that he has an interest in the process of the appointment of a candidate to the office of the Chief Justice of the Republic of Zimbabwe.

He is challenging the process and, ultimately, the composition of the panel of the first respondent which will sit for the purposes of interviewing the shortlisted candidates in a process which will eventually lead to the nomination of candidates for the position of Chief Justice.

From his founding affidavit it is clear that the applicant is aware of the constitutional framework upon which the process is anchored.

He is also aware that in terms of its constitutional mandate, the first respondent has already flighted advertisements, and identified the candidates who have been selected to attend the public interviews on 12 December 2016.

These are the fifth to eighth respondents in the application.

The applicant approached this court under a certificate of urgency on 7 December 2016 seeking a provisional order suspending the process due to be undertaken by the first respondent on 12 December 2016 pending the determination of an application that he has filed with this court.

In the main application he seeks an order directing the third respondent, as the Minister responsible for initiating the legislative agenda of the Parliament of Zimbabwe, to consider initiating a process which would result in a proposed amendment of s 180 of the Constitution of the Republic of Zimbabwe.

I have set out above the final order that he seeks presently.

The main matter is not subject of the current proceedings.

Upon receipt of this matter I directed that it be set down for hearing on 9 December 2016 with appropriate directions regarding service of the application on the respondents. On the date of hearing, I was satisfied that all the respondents cited in the application, including the Attorney-General, as the legal advisor to the Government of the Republic of Zimbabwe, had notice of the hearing.

At the hearing the first respondent raised preliminary objections on the following points: a) Urgency; b) Recusal by myself from presiding over the matter; c) That the applicant has not cited the correct parties, or, conversely, that the applicant has sued the wrong parties; d) That applicant has no locus standi to bring such an application; e) That no leave to sue the President and the Chief Justice as well as the respondent judges had been sought or granted prior to suing them; f) That the certificate of urgency was deficient in content.

At the hearing, counsel argued the above points in limine and I indicated that I will deal with them in the composite judgment.

I proceed to do so but not in the order that they were argued.

*Recusal of Presiding Judge*

Counsel for the first respondent raised the issue of my recusal, among other points in limine.

Mr Hashiti for the applicant, urged the court to find otherwise on all points raised by Mr Chinake.

After hearing both counsel on this issue, I dismissed the application for my recusal.

I gave my reasons then.

Basically, my reasons included that the first respondent had not set out any basis, factual or legal, upon which a reasonable litigant possessed of the true facts of the matter might reasonably entertain the perception that the judicial officer might be biased against him.

See Moola v Director of Public Prosecutions and Others [2012] ZAGPHC 94.

*Alleged deficiency in the Certificate of Urgency*

As for the argument that because of the alleged deficiency in the certificate of urgency, the application should fail, Mr Hashiti, for the applicant contended that the proper approach is for the court to look at the applicant’s founding affidavit and decide whether, in light of the cause of action and when the need to act arose, the court would be persuaded to still entertain the application despite the alleged deficiency.

It may well be satisfied that the certificate was not deficient.

If there is a delay in acting, the court must consider the explanation given for the delay in acting when the need to act arose.

See: Telecel Zimbabwe (Pvt) Ltd v Postal and Telecommunications Regulatory Authority of Zimbabwe (POTRAZ) & Others HH-H-446-15; Tripple C Pigs & Another v Commissioner-General, Zimbabwe Revenue Authority 2007 (1) ZLR 27.

Document Support Centre (Pvt) Ltd v Mapuvire 2006 (1) ZLR 232 (H).

In my view, the approach upon which the above cases were settled is an eminently proper one, lest many litigants suffer a denial of access to justice on sheer technicalities which leaves their causes unresolved.

The courts should be slow, and indeed they are slow, in dismissing legitimate causes on the basis of technical deficiencies that may exist on the papers.

I therefore dismiss this contention as it does not in any way resolve the issues placed before me by the applicant.

*Absence of leave to sue the President and Judges*

The first respondent argued that since the applicant has not sought leave of this court to sue certain of the respondents as required by r 18 of the esteemed Rules of this court, then his application should not be entertained.

It is correct that r 18 of the High Court Rules, 1971, requires a litigant wishing to sue the President of the Republic or any judges of the superior courts to obtain the leave of this court before he or she can issue process out of this Court.

Counsel for the applicant counter-argued that this requirement in the rules of Court is applicable when an order of a personal nature is being sought against either the person of the President or the judge.

In any event, counsel contended, where an applicant approaches the court on an urgent basis, the court, in the exercise of the powers conferred upon it under r 4 C, ought to waive the requirement.

See Tsvangirai v Mugabe HH-273-12.

Therefore in light of the extra-ordinary nature of the present application, even if such leave were required, this court ought to exercise its discretion and waive the requirement for leave.

In the present case the substantive order sought is directed, not at the respondents for which leave is required, but against the first respondent, for which leave is not required.

In that respect it is my view that there was no need for the applicant to seek leave.

In any event the respondents in whose favour such leave would operate have not claimed the need for leave on the part of the applicant.

Clearly, no order is sought against the rest of the respondents, save the first respondent.

True, the order sought may adversely affect them but only in their official capacities.

This appears to be the reason why they have not taken this suit as one personally affecting them otherwise they would have filed some form of response.

Even if I was wrong to so hold, r 4 C permits this Court to grant a departure from the rules of court in the interests of justice where it is expedient to do so.

Clearly, this would be one such case where a departure from the rules would be eminently appropriate, since, in my view, if such leave had been sought no reasonable court would have declined to grant it.

On that basis the point in limine is dismissed. “Locus standi in judicio of the applican”- Although the first respondent challenged the locus standi in judicio of the applicant to bring this application, I was unable to follow the reasoning behind the challenge.

In his heads of argument, Mr Chinake did not directly argue this point which he had raised at the outset.

He chose instead to attack applicant’s capacity to bring the application in an oblique manner by arguing that the applicant had not pleaded any known cause of action.

The reason why I find this argument difficult to follow is this.

The applicant is a citizen of Zimbabwe and is therefore entitled to the enjoyment of the rights and privileges extensively set out in the Constitution of Zimbabwe.

As I have attempted to demonstrate in the opening paragraphs of this judgment, the charter is a most liberal document with expansive rights and freedoms expressly enumerated.

In my view, this point was badly taken and merits no further consideration.

I am unable to accept that the first respondent, a creature of the same Constitution, could honestly advance such an argument.

It is important to always recall the first respondent is by implication enjoined to ensure, among other of its functions, the upholding, protection, promotion and enjoyment of the individual rights and freedoms so expansively set out in the charter.

Followed through to its logical conclusion the attitude displayed by the first respondent stands in stark opposition to its constitutional obligations.

At the heart of the main application is the complaint that although the process is lawful, in the present circumstances, it offends the constitutional values and principles on transparency, integrity and fairness.

Whether the applicant will ultimately succeed in demonstrating it in the main application is for the reviewing court to decide.

The contention by the first respondent is that the applicant has no right to seek the relief in the main matter in that he is not entitled to seek an order that the third respondent initiates an amendment of the Constitution.

The basis for this argument is that he cannot possibly succeed in proving an injury to himself by a lawful process initiated by the first respondent.

It is trite that the applicant for an interim interdict need not prove a clear right but a prima facie one though open to some doubt.

The main matter takes the form of a vindicatory action for a constitutional right.

In my view, the applicant is entitled to bring an action for the vindication of such a right, if he can demonstrate a well-grounded apprehension of irreparable harm to himself.

In the main matter, the applicant contends that should the process leading to the eventual nomination for appointment to a public office of Chief Justice be undertaken before an appropriate scrutiny of the process is concluded, although carried out in terms of the law, he would have been deprived of the right to good governance and would thereby suffer irreparable harm.

At this point I need to consider whether the applicant, in the circumstances can bring such an application in the first place. It occurs to me that where a lawful process leads to an absurd result, in the sense that colleagues select each other for entitlement to public office, as argued by the applicant, it cannot be sanctioned on the ground that it is provided for in the law.

Such an approach is irrational. I therefore dismiss the challenge to locus standi on that basis.

“Has applicant sued the wrong parties?”

In his penultimate objections, Mr Chinake contends that the applicant sued the wrong party.

The converse of this argument is that the applicant has not cited the correct parties.

In Mr Chinake’s estimation, since the first respondent does not enact the laws of this country, the applicant must lobby for a change in the law in the right quarters and leave the first respondent to execute its mandate as set out in the Constitution.

The order being sought by the applicant will conflate the roles of the different arms of State to an unacceptable degree.

The first respondent needs to enjoy its independence as much as the law as presently provided can allow.

This argument, if I understood counsel correctly, which I believe I did, boils down to a claim that the order sought will compromise the first respondent’s independence.

Again I find myself in respectful disagreement with this argument.

Whilst the first respondent is constitutionally mandated to administer the affairs of the judiciary in Zimbabwe it does not do so in a vacuum.

The fact that the first respondent is an independent commission is given in the Constitution.

I did not hear counsel for the applicant to make submission in favour of anything that could remotely be taken as suggesting otherwise.

However, whilst the first respondent is one of many independent commissions under the Constitution, it needs the co-operation of the other two arms of the State, in the spirit of comity between different branches of government.

The first respondent is the principal duty-bearer in ensuring that the intention of the law-giver; Parliament, and the Executive, and ultimately, the people of Zimbabwe, are subjected to good governance.

The third respondent, as the Minister responsible for the administration of justice and in his capacity as leader of the house, any matter which he deems appropriate for further scrutiny in the public interest and in the furtherance of due proper administration of justice and the law in Zimbabwe ought to concern him.

In this regard it will be clear that when he expresses an intention to bring for public debate, the other arms of the State ought to take notice and respond on the basis of that reality.

I am not in any way suggesting that the first respondent failed to take notice in this regard, because there is no evidence to that.

In this regard the third respondent indicates appropriately through his agent, that he has recommended to the ultimate appointing authority that there may be need to amend s180 of the Constitution of Zimbabwe depending of course on whatever the public may input during the necessary processes.

See Annexures ‘A’ and ‘B’ to the third respondent’s affidavit.

This is as it should be.

I am therefore unable to accept the preliminary objection that the applicant has cited the wrong parties or that the correct parties were not cited.

Accordingly, I dismiss the first respondent’s point in limine in that regard.

-Urgency-

Finally, Mr Chinake, for the first respondent, argued that the matter was not urgent.

The basis of this contention was three-fold.

First, it was contended that the applicant, like anyone else, was aware of the constitutional provisions set out in s 180 as far back as July 2013 when the constitution was brought into effect.

Second, and alternatively, it was contended that if he was unaware in 2013, he certainly became aware in 2014 when the first process of selecting judges for appointment was carried out in terms of the provisions of s 180 of the Constitution.

Third, and in the further alternative, it was contended that he became aware at least in October 2016 when the present process was initiated.

Put differently, the first respondent argues that on all the past four occasions when it carried out interviews to select candidates to recommend for appointment to the bench of the superior courts, the applicant came to know of the full facts upon which he could have mounted this application.

Since he did not act as far back as October 2016 when the need to act arose, he cannot be heard to pray that the matter was now urgent.

By his own admission he was aware of the present process when it was initiated then. As such the matter does not deserve to be treated on an urgent basis.

Attractive as this argument appears, it conceals the true nature of the application under consideration presently.

This application is directed at the process of selecting the leader of the judiciary of Zimbabwe, unlike the other four processes under reference.

As such, as I have tried to demonstrate above, the essence of the application is directed at the protection, promotion and upholding the integrity and fairness of the process which determines how the leader of the institution reposed with the promotion and protection of the rights and liberties of the citizenry is to be selected.

The rights that are at stake should the tenets of good corporate governance be imperilled do not only accrue to the applicant as an individual, but to the general population of Zimbabwe.

These cascade to the generality of Zimbabwe, including the respondents.

In my view the right to good governance, administrative justice, and so on, is everyone’s inherent right.

Therefore when the applicant explains that he did not pay particular attention to certain national events, in my view, he is being candid with the court.

It is not uncommon, generally, that where public affairs are concerned, individuals do not take the initiative in the vain hope that the next person will do so.

By virtue of his being afflicted by this attitude, until he realised that nobody was taking up the challenge to address the imminent threat of a possible infraction of this right, the court ought not to use the same yardstick in its assessment of whether he acted soon enough to mount a court challenge.

If the matter in issue concerned protection of strictly personal rights, then the first respondent’s contention would carry some force.

The question is whether the applicant may still obtain substantial redress in an application in due course if the matter is not treated as urgent.

This question will be determined by the facts of each case.

In the present matter the facts show that the applicant will not obtain substantial relief if the matter is not dealt with as an urgent one.

On this basis, I am prepared to treat the matter as urgent.

“Interim interdict” I now turn to consider whether the applicant meets the traditional requirements of an interim interdict.

The requirements for the granting of an interim interdict are well known.

The decisions are legion.

The requirements are the following: a prima facie right, a well-grounded apprehension of irreparable harm if the interim relief is not granted and the ultimate relief is eventually granted, that the balance of convenience favours the granting of an interim relief, and that the applicant has no other satisfactory remedy.

In this regard holmes ja said the following: “The granting of an interim interdict pending an action is an extraordinary remedy within the discretion of the Court. Where the right which it is sought to protect is not clear, the Court’s approach in the matter of an interim interdict was lucidly laid down by innes ja, in Setlogelo v Setlogelo, 1914 AD 221 at p. 227.

In general the requisites are – (a) a right which, “though prima facie established, is open to some doubt” (b) a well grounded apprehension of irreparable injury; (c) the absence of ordinary remedy.”

In exercising its discretion the Court weighs, inter alia, the prejudice to the applicant, if the interdict is withheld, against the prejudice to the respondent if it is granted. This is sometimes called the balance of convenience.

The foregoing considerations are not individually decisive, but are interrelated; for example, the stronger the applicant’s prospects of success the less his need to rely on prejudice to himself.

Conversely, the more the element of “some doubt”, the greater the need for the other factors to favour him.

The Court considers the affidavits as a whole, and the interrelation of the foregoing considerations, according to the facts and probabilities; see Olympic Passenger Service (Pty.) Ltd. v Ramlagan, 1957 (2) SA 382 (D) at p. 383D – G. Viewed in that light, the reference to a right which, “though prima facie established, is open to some doubt” is apt, flexible and practical, and needs no further elaboration.

The normative framework within which the court considers the requirements for a temporary interdict remains the same as in tradition.

As I pointed out when dealing with the objection to locus standi, I am of the view that on a broader conspectus of the matters under consideration, the applicant has demonstrated that he enjoys a prima facie right.

The content of that right might be debatable but I am satisfied that the right to fair and transparent processes culminating in an appointment to a public office is one that is inherent in every citizen of Zimbabwe.

It is enshrined in our Constitution.

I am fortified in this view by the pronouncements emanating from other jurisdictions.

Besides, Zimbabwe is a signatory to numerous international and regional treaties which speak to this subject.

The first respondent, on the other hand adopts the narrow view that this application is predicated upon an alleged violation of the law.

In it heads of argument the following appears in paragraph 60 of the heads: “60. An examination of the Applicant’s application in particular at paragraph 21, it seems evident that the gravamen of the Applicant’s application is that Section 180 of the Constitution is inconsistent with the Constitution itself and hence the need for its amendment to allow the President to appoint a judge instead of the procedure prescribed by Section. (sic). This with respect is a wrong appreciation of the law. The Constitution of Zimbabwe provides no provision for declaring a provision of the Constitution as being unconstitutional or at least inconsistent with the constitution.”

The first respondent misses the point. The point is this. Our Constitution has values. These values are not laid out or promulgated in procedural laws or practice manuals of government and its agencies. They however find expression in the will of the people through the tenets expressed in the words used in the preamble to the Constitution, as well as the specific ideals set out in the founding values and principles.

Where a State actor, such as the first respondent, fails to adhere to the same no act of wrong-doing can ever be ascribed to such failure because such failure is not visited by the sanction of the law.

The Constitution instils these values and ideals in the hope that an honest adherence to them will assure the attainment of the democratic ideals in which egalitarian equality is enjoyed by all. Viewed this way, it will be clear that the values and principles provide a moral exhortation to higher ideals for which this nation yearns for the enjoyment and realisation of our developmental endeavour.

The Constitution is therefore a live document which remains work in progress.

In the development path that is set and chosen at the national level, the Constitution provides beacons that shine the path for the citizenry to follow in pursuit of the highest stage of human development.

When therefore the Constitution speaks of peace, unity, hard work and development it is an exhortation, a call to everyone to contribute in this journey towards the attainment of set development goals.

The fact that it admonishes peaceful co-existence does not denote the imminence of war; instead it commands us to make laws that will enhance the existing peace.

Thus the legislature will, accordingly, enact laws which are directed at that goal.

The legislature cannot however anticipate every possible infraction of law that will dent the peaceful relations between and amongst us.

When a situation develops that threatens the peace, the appropriate alarm bells are sounded by the gate-keepers who are assigned to administer peace and promote appropriate legislation to deal with the exigencies of that situation.

The applicant points to the root of his complaint in the founding affidavit this way.

The fifth and eighth respondents are part of the Commission, the JSC, which is the first respondent.

The fifth respondent is its secretary as well as judge of appeal in the Supreme Court where the seventh respondent also sits as judge of appeal.

The eighth respondent, as Judge President reports to the Chief Justice who will chair the interviewing panel as prescribed by s 180.

The applicant contends that over time, relationships have formed between and amongst these individuals which may result in either prejudicial bias or favourable bias between and amongst them. He describes their relationship as “incestuous”.

He complains that in the public perception such a situation offends the integrity of the whole process thereby striking at the heart of the values of the Constitution.

The third respondent has decided to correct this situation through a proposed amendment to s 180.

Clearly, the third respondent ought to be allowed to steer that process in the interest of the integrity of the process.

How this correction is to be achieved becomes a policy issue for which the third respondent is eminently equipped to address.

In this vein, I consider that when the policy-maker indicates an intention to make provision for an hitherto unforeseen eventuality, the courts would play their role by taking notice of such intention, and allow the people’s elected representatives to initiate such processes as would facilitate that journey on the development road.

A slavish adherence by the judiciary to provisions which clearly produce unintended consequences can only serve to arm the enemy of judicial independence to the detriment of our liberal Constitutional values and objectives.

This takes me to Mr Chinake’s argument that the Constitution of Zimbabwe, 2013 recognises the independence of the judiciary as a key pillar to the application of the doctrine of separation of powers.

As such, he contended that the first respondent was mandated in peremptory terms to fill vacancies in the courts whenever they occur in terms of section 180 of the Constitution. As such, the processes initiated by the first respondent was legal, lawful and legitimate in every respect.

Therefore because of the constitutional imperative to be followed in order to fill the impending vacancy of the office of the Chief Justice, there is nothing unlawful in the processes triggered by the first respondent.

That far I agree. However this argument implies that once a process has been started, no-one can stop it, not even this court, because it is a lawful process.

In the scheme of similar documents, I regard our Constitution as a transformative charter which underscores the need for an independent judiciary.

A transformative charter has been defined as one that “..embodies a long term project of constitutional enactment, interpretation and enforcement, committed to transforming a country’s political and social institutions and power relations in a democratic participatory and egalitarian direction with the aim of inducing large-scale social change through non-violent political processes grounded in law.”

I read s 176 of the Constitution as requiring that the Constitution be interpreted in a manner that promotes its purposes, values and principles, advances the rule of law and human rights and a fundamental freedom set out in it, permits the development of the law and contributes to good governance.

Consequently, it requires an interpretive approach that takes into account, alongside the consideration of the text and other provisions on judicial independence and accountability, such elements as Zimbabwe’s historical, economic, social, cultural and political context.

In the context of the above, whilst the courts jealously guard judicial independence, the judiciary owes it to the public to be accountable politically, decisionally and behaviourally.

By political accountability I refer here to measures such as selection, tenure, conditions of service and inter-branch relations.

In our context, political accountability is secured by the Constitution as well as the Judicial Service Act, [Chapter 7:18]. The judicial code of ethics governs and regulates the other precepts of accountability.

But I digress.

In respect of the subject under discussion, legal writers have opined that judicial independence is concerned with freedom from pressure from the State, while accountability is about fidelity to the law.

These two values are complementary and there should be no conflict between them.

However judicial independence and judicial accountability have been seen as values which are constantly clashing and in tension with each other.

Some academic writers have opined that where this happens judicial independence should defer to judicial accountability in cases of conflict.

What is clear though is that an extremely autonomous judiciary becomes void of accountability and runs the risk of becoming a power above the law which is an undesirable outcome.

Indeed such a situation would make a mockery of the liberal goals secured by judicial independence.

Thus judicial independence must always be seen through the lenses of accountability.

The East African Court of Justice spoke to this balance in Baranzira Raphael v Attorney-General, Republic of Burundi reference no 15 of 2014 relying on the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) definition of good governance, thus: “..good governance is the existence of effective mechanisms processes and institutions through which citizens articulate their interests, exercise their legal rights, meet their obligations while mediating their differences.”

In this regard therefore I disagree that there should be slavish adherence to the separation of powers doctrine as Mr Chinake seems to suggest in his submission.

Just as the autonomy of independent commissions is important, their accountability is also crucial given that accountability is a core pre-condition for legitimacy of all State institutions.

As with judges, the issue of accountability arises because of their autonomy.

The Supreme Court in Kenya In Re: The Matter of Interim Independent Electoral Commission remarked: “While bearing in mind that various Commissions and independent offices are required to function free of subjection to “˜direction or control by any person or authority,” we hold that this expression is to be accorded its ordinary and natural meaning; and it means that the Commissions and independent offices, in carrying out their functions, are not to take orders or instructions from organs or persons outside their ambit.

These Commissions and offices must, however operate within the terms of the law: the ‘independence clause’ does not accord them carte blanche to act on whim; their independence is, by design, configured to the execution of their mandate, and performance of their functions as prescribed in the Constitution.

For due operation in the matrix, ‘independence’ does not mean ‘detachment,’ “isolation” or “disengagement’ from other players in public governance.

Indeed for practical purposes, an independent Commission will often find it necessary to co-ordinate and harmonise its activities with those of other institutions of government, or other Commissions, so as to maximize results, in the public interest.

Constant consultation and co-ordination will ensure a seamless, and an efficient and effective rendering of service to the people in whose name the constitution has instituted the safeguards in question.

The moral of this recognition is that commissions and independent offices are not to plead ‘independence’ as an end in itself; for public governance tasks are apt to be severely strained by possible ‘clashes of independences”

One must accept, as I do, and agree with Mr Chinake to the limited extent that for the first respondent to be effective in the execution of its mandate it must operate independently.

From the foregoing I would therefore add the rider that it must also be accountable.

As is now widely accepted world-wide, there may be the possibility that the independent commissions may engage in corruption or pursue partisan interests rather than the public interest.

This speaks to the need for oversight over independent commissions given the reality that when any State organ is left unchecked it can run amok and perpetrate the very ills it is mandated to curb.

There is also a need for political accountability, in the form of accountability to the elected representatives of the people. In a democracy all parts of government ought to be accountable to the people.

This is driven by the reality that out of the social contract, government in theory is an agent of the citizenry in a democracy.

This raises the valid concern of the need for accountability to democratically elected officials to give independent commissions, like the first respondent, legitimacy.

I turn now to consider the impact of the affidavit placed before the court on behalf of the third respondent, the Minister of Justice and Legal and Parliamentary Affairs.

It was deposed to by the permanent secretary in the Ministry of Justice and Legal and Parliamentary Affairs.

In it is revealed a clear intention to canvass the public for a change in the law.

Such change, so it would appear, may lead to an amendment proposed in the form of the draft annexed to the affidavit as annexure ‘A’.

There is also annexed to the same affidavit, a draft memorandum addressed to Cabinet highlighting the principles of the proposed amendment to the Constitution of Zimbabwe.

Counsel for the first respondent urged the court to disregard these drafts since they do not constitute the law.

It is a correct statement of the law that internal memos and draft bills do not constitute part of the law.

It is true, too, that the memo to cabinet does not bear the third respondent’s signature.

Consequently, so the first respondent’s argument went, these do not add value to the present proceedings since the law is what is represented in s 180 of the Constitution.

Mr Chinake, for the first respondent persisted that the first respondent cannot be stopped from executing its constitutional mandate on the basis of these drafts.

If this argument is seriously made then it reflects poorly on the first respondent’s perception of its role, which would be unfortunate because it suggests that even in the face of clear intention of the policy-makers, the first respondent is bent on proceeding with a process which the applicant is challenging and which challenge appears to have caught the attention of the policy-maker.

It does not need rocket science to see the genesis of a possible but hardly necessary conflict between the two arms of the State.

Once a court is briefed on the intentions of the policy-maker, as in the present case, where the court is seized with an application by a private citizen regarding the probable infringement of a prima facie right, it would be remiss of the court to disregard that advice when deciding whether to grant the relief sought or not.

The applicant’s fears are quite clearly vindicated by the first respondent who appears quite determined to achieve, for some obscure motive of its own, a fulfilment of its constitutional obligation against opposition.

As an example, Mr Chinake had the temerity to instil the fear of a constitutional crisis should the process be stayed.

This crisis probably resides in his client’s imagination only because the Constitution clearly provides that in the absence of the Chief Justice, the Deputy Chief Justice acts in his stead.

It also provides that in the absence of the Deputy Chief Justice, then the next senior judge acts as the Chief Justice and so on.

I am not persuaded that any such crisis will envelop this country should the process be stayed pending the determination of the main matter.

Further I am satisfied that the balance of convenience favours the applicant.

I come to this conclusion, not on the strength of the annexures to the third respondent’s papers, but on the lack of opposition from the third respondent.

In the result therefore I am satisfied that the applicant is entitled to the relief he seeks.

It is therefore ordered that: Pending the determination of this matter, on the return date, the following relief is granted:

1. That the first respondent be and is hereby interdicted from conducting interviews set for 12 December 2016 which interviews are for the ostensible purpose of submitting names purpose of submitting names to the President of the Republic of Zimbabwe for his consideration in appointing the Chief Justice of Zimbabwe.

2. There will be no order as to costs. Venturas & Samukange, applicant’s legal practitioners Kantor & Immerman, first respondent’s legal practitioners. The Herald