By Kevin Sieff | Washington Post |

In one of the world’s oldest autocracies, Itai Dzamara set a dangerous goal: He would bring down 91-year-old President Robert Mugabe.

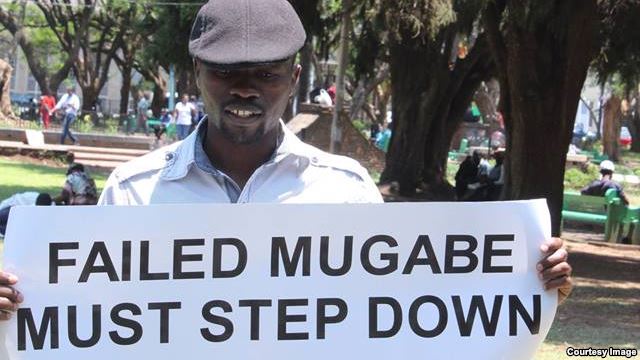

Starting last year, Dzamara, 36, marched through this city’s streets holding a placard reading “Mugabe must go.”

He demonstrated in front of parliament. He delivered a petition to the president’s office, demanding his resignation. He rose to fame for being either brave or reckless, depending on whom you asked.

For a while, it seemed he would get away with it. Dzamara was briefly arrested. He was beaten by police officers. But his crusade wasn’t stopped.

Was Zimbabwe becoming more tolerant?

Mugabe’s regime has been accused of killing hundreds of its opponents since he rose to power in 1980, with the ouster of a white-minority government. The United States and the European Union have long tried to curb political violence here, imposing sanctions and criticising elections marred by intimidation.

But it had been years since the Zimbabwean government’s last major crackdown.

Dzamara appeared to be a heartening symbol: an activist who was finally willing and able to criticize Mugabe, 35 years after the president took office.

“It seemed like we were given a respite,” said Morgan Tsvangirai, leader of the country’s main opposition party.

Then, in January, Dzamara suddenly grew anxious, telling a group of friends that he wasn’t sure how much longer he would be around.

“You need to be prepared to go on without me,” he said, according to one of the friends.

Two months later, on March 9, six men in plainclothes grabbed Dzamara while he was getting a haircut. They handcuffed him and threw him in the back of a white truck. It is the last time he was seen.

Dzamara’s disappearance has become the biggest political scandal in Zimbabwe, a source of endless speculation.

The government says he likely staged the kidnapping himself, thinking it would galvanise the international community against Mugabe. Many of Dzamara’s friends say he is probably a victim of the country’s secret police, killed just as he was becoming a rallying point for government critics.

The U.S. Embassy has called for a thorough investigation. The E.U. has said it is “deeply concerned.” Dzamara’s lawyers plastered the city with posters of him, promising a reward if he was found. They were quickly torn down.

In April, news spread that Dzamara’s body had been found on a farm outside of Harare, but it turned out not to be him. Later, there were reports that he was spotted in Botswana. “He’s enjoying life,” said Paradzai Chakona, a prominent member of the ruling party. That story also proved false.

The police have denied they have any information about Dzamara detention or whereabouts.

But government critics say the timing of the disappearance is hardly coincidental. Dzamara vanished just after one of the most dramatic political shifts in the history of the Mugabe regime, a deep rupture in the ruling party.

“For Mugabe and the government, it’s only when they feel under threat that they crack down,” said Dewa Mavhinga, a researcher for Human Rights Watch. “And Dzamara posed a threat.”

Dzamara was a baby when Mugabe came to power. It was a moment of enormous promise for Zimbabwe, which had cast off a legacy of British colonialism.

Mugabe, who had been a guerrilla leader in the war against the white-ruled state, pledged to transform his country into a model for Africa.

“Independence will bestow on us a new personality, a new sovereignty, a new future and perspective,” Mugabe said in 1980.

As Dzamara grew up, he became disillusioned with that new personality. He saw the country’s elections as rigged, its policies enriching only a circle of top officials, itsinflation so extreme that the central bank printed 100-trillion-dollar notes.

He began writing for one of the country’s independent newspapers, which were permitted to criticise the government, even though public demonstrations weren’t tolerated.

Many older Zimbabweans still thought of Mugabe as the war hero who brought them independence. Dzamara’s father, a civil servant, defended the regime in arguments with his son — a generational divide still reflected across the country.

Dzamara is slim with boyish features and a wide smile. He consumed books like Nelson Mandela’s autobiography and uncensored histories of Zimbabwe, which circulated quietly between friends. With a touch of irony, he named his dog Zec, after the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission, which he considered corrupt and ineffective.

In October, he abruptly quit journalism, writing on Facebook that he was about “to stand up to an urgent and pressing national challenge.”

He didn’t tell anyone what his plans were. Then, on Oct. 17, 2014, Dzamara went to the city’s main plaza, near the president’s office, with a placard demanding Mugabe’s resignation.

He named his movement “Occupy Africa Unity Square” and he returned each morning, accumulating a small group of followers. The unmarked secret police headquarters was only two blocks away.

“My first thought was that I couldn’t believe someone had the guts to do this,” said Dirk Frey, a university student who would join Dzamara’s demonstrations.

Still, there were signs that the government might be ready to permit dissent. It had passed a new, progressive constitution, approved by the opposition that for the first time imposed term limits.

The E.U. had agreed to resume aid to Zimbabwe after a 12-year hiatus — a reward for what it deemed an improvement in democratic behavior.

Then, in December, the ruling party, Zanu PF, seen for years as indestructible, suddenly appeared to fracture. Mugabe accused his vice president, Joice Mujuru, and several other top officials of plotting an assassination attempt.

He fired dozens of party loyalists and announced that he would run again for president in 2018, at the age of 94, surprising many who had expected him to announce his retirement. His wife, Grace Mugabe, 49, was given an important position in the ruling party, a move that fed speculation about an intensified war to succeed the president.

After 35 years, it seemed the regime might be eroding, the victim of an internecine conflict.

“The end of Zanu PF is drawing close,” read an editorial in a local independent daily.

Dzamara stepped up his small movement’s actions, marching through downtown Harare, returning to the president’s office, posting photos online of the bruises inflicted by the police beatings.

In the past, when the Mugabe regime was threatened, it lashed out. In 1983, Mugabe orchestrated the killing of thousands of his opponents in western Zimbabwe.

The crackdowns continued through 2008, when Mugabe trailed Tsvangirai in the first round of the presidential election. In the weeks before a run-off vote, the government and its supporters killed more than 100 of its political adversaries, according to human rights groups, and Tsvangirai was forced to withdraw from the race.

“Some say Itai was a small figure, but what he represented was much bigger,” Tsvangirai said. “He was seen as a threat, and he was targeted as one.”

Jestina Mukoko has been watching Dzamara’s story unfold from her fortified office in Harare, where access to each room requires a fingerprint scan. She knows to be careful. Seven years ago, she was the one who disappeared.

Mukoko is a researcher for the Zimbabwe Peace Project, a non-governmental organization focused on political and gender violence. I

In December 2008, she delivered a report on the government’s abuse of its opponents. A few days later, a truck full of men in plainclothes arrived at her door at 5 in the morning. She was blindfolded and driven away. It was the beginning of a 21-day captivity, during which she was tortured in a nondescript government guesthouse, Mukoko said.

“The only recent example we have at all like Dzamara’s is Jestina’s,” said one of Dzamara’s lawyers, Dzimbabwe Chimbga.

The government later said it detained Mukoko because she was a spy for the opposition party. But the Zimbabwean Supreme Court concluded that the government “violated [Mukoko’s] constitutional rights.”

“It did seem like things were getting better,” Mukoko said from her office, where photos of her meeting Michelle Obama and then-Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton decorate the walls. “Then Itai was abducted.”

Early last month thousands of people poured into the stands at National Heroes Acre, a hallowed burial ground, to hear Mugabe commemorate the fallen veterans of Zimbabwe’s war for independence.

“Look around,” said Saviour Kasukuwere, the minister of local governance. “Our party has never been stronger.”

Mugabe arrived in a Mercedes limousine. Thousands rose to their feet. The old man walked slowly up a series of stairs.

“We are delivering democracy on a platter. Do you take it?” he said.

For the last six months, the government has scoffed at allegations that it eliminated Dzamara. Mugabe’s spokesman, George Charamba, said Dzamara wasn’t important enough to be considered an enemy of the state.

“It leaves the government wondering whether or not the whole incident is not a politically calculated contrivance” by the opposition party, Charamba told reporters.

But former members of the party, now expelled, say Dzamara is exactly the kind of person the government would go after.

“To me, it has to be state security that abducted him,” said Rugare Gumbo, a former government spokesman.

“I think Dzamara was an embarrassment to ZANU-PF, and that’s why he had to disappear,” said Didymus Mutasa, the former head of Zimbabwe’s Central Intelligence Organization.

“I know there are several ways to make people disappear in this country,” the former spy chief said obliquely.

In August, the U.S. government issued another statement, this time using sharper language, calling for Dzamara’s “immediate and safe return.”

A few days earlier, on Dzamara’s 36th birthday, his family and friends had gathered in the same plaza where he had waged his demonstrations. They wore shirts that said “Missing!” with a picture of his face.

Dzamara’s supporters have celebrated his commitment to the cause, rather than depicting his actions as reckless. But when she’s away from the group, his wife, Sheffra, says she should have sensed the danger.

“I should have told him to stop the activism,” she said.